Together for Green & Complete Streets

by Michael Anderson

Wisconsin is a state with a rich connection to its natural spaces; for people who ride bikes, this experience is often linked to trails, waterways, and native ecology. Indeed, the development of many of our state’s trail systems mirror the natural flow of our many rivers. Yet, this link between biking and ecology seems to dissipate when we discuss the complete street movement. Indeed, biking advocates and other environmentalists have been pitted against each other in discussions of our public right of way.

Recent examples include controversy in Milwaukee over protected bike lanes on Lake Drive as well as debate leading into the Humboldt Avenue Reconstruction. Yet, whether championing our tree canopy or fighting for protected bike lanes our shared vision often lies within values of accessibility and environmental justice. Investments in complete streets carry with them great potential for ecological restoration. As such any opportunity to peel back the pavement is an opportunity to build an environmental coalition. Still, we are in a precarious time as massive investments in protected bike lanes and other traffic calming infrastructure bring with them a potential for “bikelash” setting us back in our goal to build more resilient and active communities.

As result of covid relief funding such as ARPA and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) this time of investment will also be a profound moment of learning for safe streets practitioners as we look to our peers in other states to see how they have built coalitions and leveraged funds to maximize the environmental impact of their transportation funding. In 2023 Greg Woltman, a Research Project Coordinator at the Alan M. Voorhees Transportation Center in New Jersey suggested funding complete streets projects from a provision within the BIL called the “Promoting Resilient Operations for Transformative, Efficient, and Cost-saving Transportation Program” or PROTECT for short. While one community in Wisconsin did receive discretionary funding, for the Little La Crosse Watershed Infrastructure Resiliency Initiative, the law provided much more funding to each state with a formula. These formulas are often complicated and allow for state governments to redirect the funding to other federally funded projects. Together, as a broader environmental coalition we stand a greater chance of maintaining our share of such funding in the rare opportunities that political winds do provide.

I sat down with Willie Karidis, director of the East Capitol BID and Director of Route of the Badger to discuss ways that Milwaukee is creatively funding this confluence between Green Infrastructure and Traffic Calming. As part of his work building out trail networks in SE Wisconsin Willie frequently partners with programs offered by Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD) as well as investing time and resources directly into grassroots community leaders such as local churches and neighborhood groups. Willie advised the importance of getting creative with partnerships, especially when political obstacles stall your communities vision, such as working on a state owned road. He pointed to a situation in which state regulators said that nothing, plants included, could be larger than 36″ in the median of the road. Yet, the larger community vision and collective resources of stakeholders helped move greater and bolder green infrastructure into their plan. The planning phase alone often predates funding for a project; depending on the conversations in that early planning phase the direction of funding sources and potential partners is highly influenced. Having a bold environmental concept early in a planning process gives advocates the best chance of working together and coalescing around a shared vision as well as identifying creative funding options. As Willie says, “I’ve learned over the years that you have to get it in the plan.” In light of his words let’s look towards some of Milwaukee’s recent advancements in the intersection of Green Infrastructure and Complete Streets.

“I’ve learned over the years that you have to get it in the plan.”

Green Infrastructure & Traffic Calming Around Milwaukee

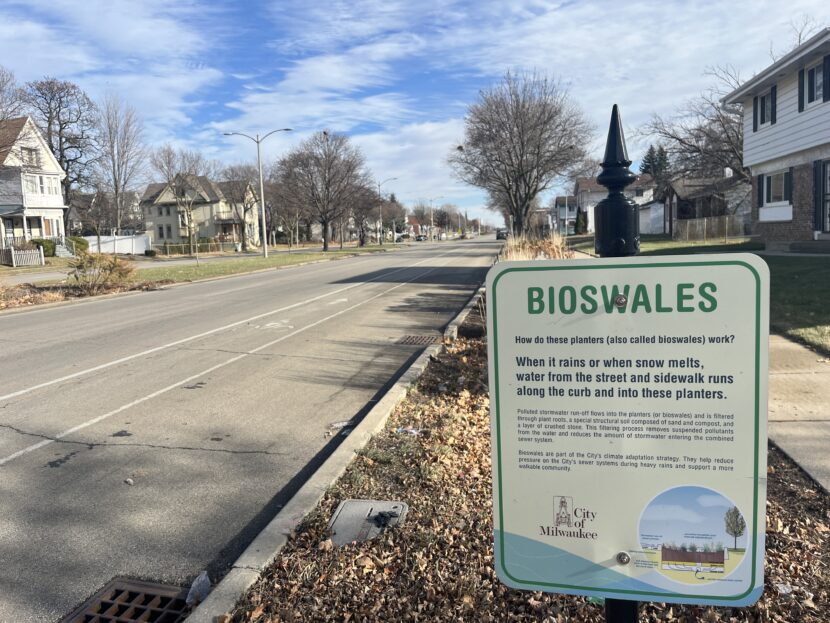

These bioswales on Highland Avenue absorb rain water and are one of many projects aligned with Milwaukee’s Green Infrastructure Plan . While these bioswales outdate the City of Milwaukee Complete Streets Policy the scale provided by the cargo bike illustrates that this section of roadway was overbuilt to accommodate cars. This is especially highlighted by the lack of any cars parked on this block.

Fortunately, this section of roadway will soon have a road diet similar to the successful rapid implementation road diet rom 35th to Vliet. Yet, this large section of pavement illustrates a perfect example of where a larger generational project, where a road structure gets entirely rebuilt such as Walnut Avenue, provides even greater opportunities for environmental collaboration. Both Highland and Walnut Avenues are featured in the Bike Fed’s videos explaining new complete street features; the first minute gives a great perspective of these roadways and emphasizes that both green and complete street infrastructure are intended on returning our streets to the people.

This is highlighted in a WUWM BublrTalk story on this subject from May 2024. Audrey Nowakowski, in an interview with DPW’s Kurt Sprangers, explains the ecological benefits of bioswales and Milwaukee’s ongoing investment. In the interview Kurt says, “you’ll see some of the traffic calming projects that are going on, we’re looking to see…how can we green those up a little bit so it’s not just a plain concrete island?” Indeed we are seeing these investments popping up right now.

Recent infrastructure on the Northside of Humboldt Park in Bay View demonstrates how a road reconstruction can include rain gardens/bioswales, parking pods, as well as shortened crossing distances and accessible curb cuts. According to Nacto, shortening the crossing distance to parks is an important accessibility issue, helping reduce speeds, increase both visibility and rates of yielding. They have new recommendations for such projects in their Urban Stormwater Guide.

The corner of Wisconsin Avenue and Vel Phillips Avenue across from Milwaukee’s convention center has recently seen the transformation of a paved parking lot into a permeable plaza dedicated to one of our local civil rights champions, Vel Philips. Not only does this space help restore our natural water table and expand our tree canopy but it includes a Connect 1 Bus Rapid Transit Station, as well as providing a Neckdown, a narrowing the road, as one approaches an intersection with a lot of pedestrian activity.

This traffic circle on Washington Street & 11th Street is part of the City of Milwaukee Bike Boulevard program. While we have seen traffic circles popping up recently in neighborhoods across Milwaukee, many of them do not have plants in the center. Rocks have been added to this design to add extra protection from cars damaging the tree. Studies show that trees are also an important tool in traffic calming. UK Based Trees for Streets help explain the linkages between trees and traffic calming. Essentially, trees both make us feel calmer but also act to slow our speed when in motor-vehicles. Conversations about bike infrastructure should include conversations about trees!

Just down this new bike boulevard at Doerfler School another key agent of change is present, ReFlo. Their work on Green Schools has been instrumental in introducing the concept of traffic gardens to Milwaukee. Their belief in traffic gardens helped MPS and the Bike Fed expand to paint traffic gardens at over 80 schools with aforementioned ESSER funds. Their work to reduce pavement and to bring nature back to playground aligns well with young people reconceptualizing public space. The installation pictured above of a rain garden as the centerpiece of the school entrance, now helps establish a natural corridor down the Washington/Scott Bike Boulevard and to nearby Mitchell Park. The Scholars pictured above participated in Bike Fed Camp in 2020. They now have a traffic calmed route to Lake Michigan and Harbor View Plaza that begins and ends with native plants.

The Becher Overpass Project a partnership with many large partners including MMSD, DPW, and WisDOT, established a massive water reclamation project, with walking spaces, new trees that will soon be visible from the interstate above, as well as being instrumental in a road diet along Becher. Art work on the pillars both at Becher and at Washington on the aforementioned Bike Boulevard feature art highlighting both themes of roadway safety and our communities connections to water.

Gathering the Waters

While it is great to celebrate all of this amazing work it is also important to remember that Wisconsin is still spending much less than the national average on bike/ped projects, as noted in the 2024 League of American Cyclists state rankings. While Wisconsin still lags the nation in investment in active transportation this is an especially important time as we enter an uncertain political climate with new generational investments at doubt. We need to look toward to our regional and hyperlocal coalitions as places to fund and sustain green infrastructure projects. This was another area Willie Karidis said we have opportunities; in how we message and partner around maintenance of green infrastructure. Where small obstacles may present themselves so do opportunities for community ownership and buy-in. Creative partnerships in the environmental field are abound, as evidenced by UWM’s Watermarks program, which brings together an intersectional group from across fields in Milwaukee in the realm of public art, water, and health. This Summer Bike Fed High School students will work with artists at Watermarks on two decorative crosswalks, bringing together the narrative of traffic calming and our connection to water.

While strong partnerships do exist across the city it is important to recognize that much of the pushback against complete street projects in Milwaukee has happened when front end engagement may have been lacking and often with quick paint and post projects; yet the lessons we have learned from these have been invaluable in terms of data collected. One thing is certain, that the key to meeting our environmental goals, is to work on them early and to work on them together.